- Home

- Susan Kreller

You Can't See the Elephants Page 4

You Can't See the Elephants Read online

Page 4

“The Brandner kids across the way, I think something’s up with them.”

“What, dear? What are you talking about?”

“I don’t know, but I think the parents are doing something to them.”

“Not the Brandners! What are you talking about? They were the king and queen of the spring festival just four years ago. We decorated the whole street just for them.”

“I’m telling you, I actually saw it. Through the window.”

“This keeps getting better. So you go around looking in people’s windows, do you?”

“I heard screams, that’s why. Mrs. Johnson, you must have noticed something. The Brandners live just across the street from you. Haven’t you ever heard anything?”

“I’m going to tell you something. There was someone else here once, who suspected such a thing. She lived right next to the Brandners. Then two years ago, she moved away to her daughter’s because she was so ashamed.”

“Elsa.”

“Elsa Levine, yes. How did you know? Well, it doesn’t matter. At any rate, Elsa finally realized what people thought about what she’d said. It was slander. So watch what you say.”

Mrs. Johnson looked furious. Her throat was red, and the tufts of grass she’d been holding lay on the ground. But she was also concerned. Maybe I seemed pale. Then she went on, more softly and quietly.

“My dear, it could be that there is screaming from time to time. The Brandners have problems with their children. It happens in the best of families.”

“Yeah, problems, but not like this. This doesn’t happen in the best of families.”

“Well then, everyone must judge for himself. Besides, take a look. The children are fine. Julia and Max don’t want for anything. Their clothes are always clean and there’s a large garden behind their house. The Brandners are awfully nice people. Don’t worry, everything is fine. The— Oh! Christian, hello. How are your lilies?”

He stood there, Mr. Brandner, maybe twenty yards away, on the small path beside his hydrangea patch. It was impressive how fast Mrs. Johnson was able to put a neighborly smile on her face. “So, are they wilting yet, Christian?”

It was also amazing the way Mr. Brandner replied, with a smile, “All good, Rose, all good. None of them hanging their heads yet at our house.”

He seemed completely different from the way he’d been the last time I saw him. His face wasn’t red. He was almost nice, even. I’m sure he was considered good-looking and friendly. He simply looked like a neighbor, chatting good-naturedly about lilies.

I felt like the net in a tennis game of words between Mr. Brandner and Mrs. Johnson, Mrs. Johnson and Mr. Brandner, back and forth and back again. I looked over at the Brandners’ house and wondered if I had imagined it all. I wanted the answer to be yes.

Then I saw a curtain move in the window beneath the gable. It was only just barely noticeable, but I felt something. What I mean is, I felt it for real, all through my body, everywhere. I had no idea when, but at some point Mrs. Johnson had pressed a bouquet of asters into my hand. I raised my hand and pushed the asters back at Mrs. Johnson, hoping to spoil her pleasant conversation with Mr. Brandner. I knew no one here was really interested in Julia and Max.

14

Nine.

One.

One.

Nineoneone.

I knew perfectly well you weren’t allowed to call the police for just any reason.

Never call the police for fun, my grandmother had told me when I was a little kid. They’ll find out. They can tell who’s calling. They’ll find out in the end. They get upset when people play pranks on them, very upset, and they’ll be upset with you. But after my conversation with Mrs. Johnson, I didn’t care if anyone got upset with me. All I wanted was for someone to pay attention to me.

The question was what I should actually say when I finally had a police officer on the line. Hi, I’m Mascha, and could you please come rescue Julia and Max? I sat myself down on the bed in the guest room for a long time, after talking to Mrs. Johnson, and thought about it.

Then I dialed the number, nine one one, but hung up without even waiting for the first ring. It wouldn’t work. Nothing would work. I let my cell phone fall from my sweaty palm to the bed and lay there staring at it for ten minutes. I don’t know what made me pick it up again, maybe the same thing that made me give Mrs. Johnson back the flowers, but finally I took the cell phone in my hand and dialed again: nine one one.

“Nine one one, what is your emergency?”

“Um, hello?”

“Who’s calling?”

“I saw something.”

“What is your name?”

“Mascha, Mascha Wernke. I saw something.”

“Okay, just remain calm and tell me what you saw.”

“I saw children, children with blue bruises and a cut on the head. I also saw . . .”

“Have you been involved in a fight?”

“Um, what?”

“What is it with you kids? We get these calls constantly. Three already today.”

There’s something about adult voices that totally throws me. There’s this certain impatient tone they have. Sometimes I hear it from teachers or even the lady at the bakery. It cuts my words into tiny little pieces, and I begin to stutter, and I have nothing to say anymore because anything I’d say would sound ridiculous. It hadn’t happened to me with the people I’d spoken to about Julia and Max so far, but the operator’s voice was one of those word-chopping voices, and with every stuttered sentence that I sent out through the telephone line, I just made things worse.

“Um, yeah, no. I’m not just calling, see? I’m not just calling like that!”

“What is it then? Someone’s gotten into a fight, is that it?”

“No, no one’s actually getting beaten up right now. But it happened, you see. And, um, really, uh, often. It really happens very often. I think.”

“Little girl, how old are you? Are you trying to play a joke?”

And then I did the dumbest thing I could have done. I began to laugh. That sometimes happened to me. At school one time, there was a teacher, the teacher who was in charge of recess. She came storming into our noisy classroom and yelled at us so badly that I burst into laughter out of fright. I was called up to stand in front of the classroom and got yelled at some more, even though I was the only one who had been sitting completely quietly just before, when all the other kids were making so much noise.

It was like that this time, too. I was so torn by what I was doing, so upset, that I couldn’t help laughing. After that, I hung up. I had blown it, blown the whole thing.

I wasn’t able to do it. I wasn’t able to open my mouth at the right moment and make myself heard by the right people. Or by anyone at all. I’d made a few attempts, and I’d spoken to my grandparents, but there was no point. No one wanted to know anything about the people who owned the car dealership and how they beat their children so badly they had to spend their entire days hiding their wounds beneath long hair and long sleeves.

Time passed.

Weeks.

I was tired, just tired. Really, all I wanted was to be left alone, to be tired all by myself. To do nothing. That was all I wanted when I saw Julia and Max in the playground again one day. Julia turned to me with a deathly pale face.

“Do you want to run away?” she asked. “I really want to run away to someplace where no one will find us.”

15

Julia’s face was so pale that I was scared to respond. After a minute, on that sticky, hot afternoon, it wasn’t clear to me anymore exactly what question she had asked. I just stared at her and said nothing.

“Mascha?”

“What? Oh yeah, do I want to run away? I don’t know, probably not. How are you going to find a place like that, anyhow?”

“Maybe Canada. Or Madison. A

kid who used to be in my class lives there now, and everything’s always good with him.”

“How do you even know?”

“You can just tell that kind of thing!”

“All right, then, Madison. It’s a lot closer than Canada.”

“We could take the bus. The bus goes everywhere. One time, we went—”

“What? Julia, did you run away before? Have you already tried it?”

“Are you nuts? We’ve never gone anywhere alone!”

The way Julia said that, both fearful and hopeful, and the noise that Max let out, which sounded like he had something to say on this subject—all of that made me suspect that Julia and Max had, in fact, run away before. But if they had, they hadn’t gone far enough. Because they wouldn’t still be here, in the playground showing their sad faces to the sun. Julia was sitting next to me on the fort, as usual, and Max was kneeling a few yards off in the sand and poking around with a red toy shovel that someone must have left behind. I couldn’t see his face because he was sitting with his back to us. On his neck there was a great roll of fat, which somehow made me sad. I’d only seen rolls of flab like that on old men.

I sat there feeling numb. My arms, my legs, my thoughts, everything was numb. I didn’t want to see Max go crazy or Julia get serious again. Mostly, I just wanted to be able to sit on my fort all by myself and listen to my music. That had always been enough before.

Not much more was happening on that early afternoon at the end of July. It was so hot. Every now and then something that you could hardly call a breeze passed us by. A couple of bees buzzed, a girl cried, and in the distance a car drove past. There were fewer mothers and children at the playground than usual. There was no shade there, but Max continued to kneel in the glowing-hot sand. It must have been painful, I thought, but he didn’t seem to feel it, I guess because he was an expert at pain. Not even the hot sand could get a reaction out of him.

And then suddenly, on some sort of whim that surprised even me, I said to Julia, “Come on, let’s play a game. Let’s play Running Away.”

16

Play Running Away? What do you mean?”

“You know, Running Away. Haven’t you even done that before?”

“But how do you play it, Mascha? Either you run away, or you don’t. You can’t play it.”

“We just have to imagine everything. First of all, something awful that we have to run away from. And then we imagine a knapsack that we’ve packed, and a map and then some money in case we get hungry on the way. We just have to imagine it all. And after we run away, we just come back.”

“I don’t know. Where should we go? I’m so hot.”

“Don’t worry. I know where. I know exactly where we can go.”

I could tell Julia was thinking, Just leave me alone, Mascha. Her brother was kneeling peacefully in the sand, completely unaware.

“Maybe he wants to come along.”

“Maybe he doesn’t want to go anywhere.”

“Maybe he wants to lie down on the sand and die because he hasn’t done anything in such a long time.” But then I added in a whisper, “I have a surprise for you. The place we’re going to run away to, it’s a surprise, and a secret, too.” And with that, Julia became interested.

“A secret. Okay, a secret sounds good. Let’s go.”

So we went.

We played Running Away. We stomped through the sand and then slowly made our way along a path that only I knew about. I went first, Julia shuffled along behind me and last came Max, wheezing loudly.

The playground was at the edge of the neighborhood, so we didn’t pass by many houses as we played our game. Because of the heat, the windows of the few houses we did pass were hidden behind blinds. There was no one out to see what miserable runaways we were as we trotted through the neighborhood.

Then we left the houses behind and came to a cornfield. The green stalks towered over us, and Max’s wheezing grew louder. Then the corn became a field of grain, and everything around us shimmered gold.

The barley field. It was enormous, the size of three football fields. The stalks went up to our thighs, every one was the exact same height, and they went on forever. And right in the middle, in the middle of this giant field of grain, was a small blue wooden house. It wasn’t much more than a shack, but there in the vast field of gold-gray-brown, it stood up like a too-tall cornflower. I said to Julia and Max, “There it is, see?”

Silence.

Julia was not the least bit impressed. When she found a few words for me, she simply murmured, “Oh, that. Everyone here knows that house. Everyone walking down the street can see it, but no one ever goes inside.”

Even Max gave a disappointed nod. Who knew what he had imagined the secret spot would be—someplace with chocolate or something like that, not the edge of a field with a view of a useless blue shack that he’d seen a hundred times before. He pulled up a few stalks of barley, stripped off the kernels with his fingernails and threw them to the ground. Julia stood indecisively in the middle of the dusty path through the field.

“So, what now, Mascha?”

“Well, this is it.”

“What are we supposed to do here? Stand around and look at that shack?”

“I haven’t told you that part yet.”

“Come on, Mascha, let’s get out of here. We’ve been here before. Everyone knows about that house.”

I had imagined it differently.

True, my idea of pretending to run away was not the best, but that blue house, it was really something. I wanted to cry or scream or throw myself down in the barley field. A few angry thoughts flew through my head, and I was about to say that Julia and Max didn’t deserve a secret place like this, so come on, let’s go. Then I saw Max’s red face, which seemed to badly need a secret spot.

“Sure,” I said. “Everyone knows about it. But only one person has the key, and that person is me.”

17

I had discovered the blue house two years ago, though it wasn’t exactly a discovery, because I had always known about the blue house too. It was part of the neighborhood, just like the raked front yards and the barley field it stood in, and the green sea of corn growing between them.

So it wasn’t that I had first discovered the house two years ago. More like that was when I’d come up with the idea that there were other uses for blue houses in barley fields than just looking at them. A person could, for example, fight through the stalks of grain, find that the door of the house was locked and then have the luck to find a rusty key under the large stone by the door. I was certain the blue house couldn’t belong to anyone because it was so filthy inside and, after a little thinking, I came to the conclusion that effective immediately the house would have a new owner: me.

It was good that I had the key, because it seemed to make Julia and Max suddenly believe that this was a good place for us. It was a place where you could spend an entire afternoon. We followed the path to the edge of the field, turned left and walked a little farther before we actually entered the barley. I’d realized two years ago that if you wanted to keep a blue house in the center of a field a secret, you had to approach it as stealthily as possible. Every step in a field of grain leaves a footprint behind it, but those footprints could at least be made where they wouldn’t be noticed.

Under our feet, the stems cracked. Over our heads, the sun burned. When we arrived at the house and I had unlocked the door, I heard someone say something bizarrely normal. It didn’t seem possible that it was Max who cried out loud, “Oh man!” He shoved his way past me and then went carefully, slowly through the room, as if he were afraid he might break something by stepping on it. There wasn’t much, just a few pieces of beaten-up furniture. When I first started using the house, I spent an entire week cleaning it. Back then, there had been nothing but a damp mattress, a scrub brush, an old rag and not nearly enough water, sinc

e it had to be hauled there by me in plastic bottles.

The whole room had been full of spiderwebs, which I’d removed from the corners with the help of some long sticks. I had taken the old mattress outside, beaten the dust out of it and dressed it up in an auburn-colored bedsheet. I’d also cleaned the single window, which had been so filthy you couldn’t tell it was a window anymore. Outside the window there were iron bars, who knew why. Maybe someone had once stored something valuable here, maybe jewels or something, and they brought the mattress to use while keeping watch over it.

In the meantime, many more things had come to the blue house. Most of them things I had found on the street: the striped carpet with the fringe, the standing lamp that didn’t have any place to plug it in, the small shelf and bleached-out painting in the gilt frame. In one corner was a bucket from the big cleanup, and on the shelf lay an old wool blanket, a stack of comics, a tin can full of cookies and a bottle of soda. I’d brought the cookies and the soda, which must have been boiling hot, at the very beginning of vacation, but they were still there because I hadn’t been back to the blue house all summer.

I was used to this room, but when I saw Julia’s and Max’s reactions, I thought to myself that everything was really beautiful. It all fit so well together. Max said again, “Oh man!” The reddish-brown of the bedcover and the gilt-framed picture shone. I’d never really noticed it before, but the shelf and lamp were in exactly the right spots. The room seemed like a place where a person could be safe—where Julia and Max could stay, just like that. Julia actually seemed to feel at home there. She let herself plop down on the mattress.

“Mascha,” she said. “This is crazy. Are the cookies still good?”

Max said nothing. He just stood there and smiled.

18

It was hot in the room, and old and musty smelling. Many years of rainstorms had left the wood damp. I opened both the door and the window, but there was no breeze outside, so it didn’t help much. Even so, the heat was different inside than out. It was easier to handle, and the smell was only bad for the first few minutes. Max was sweating, as usual, and his entire head was bright red, but his breathing was calm. He went to the bookshelf and took the comics down, one by one, like they were valuable.

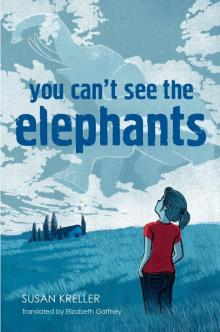

You Can't See the Elephants

You Can't See the Elephants