- Home

- Susan Kreller

You Can't See the Elephants Page 3

You Can't See the Elephants Read online

Page 3

Beyond that, it was all about how the car dealership wasn’t doing well and they couldn’t take a summer vacation like they always had and how everything was going badly. I also heard how Mr. Brandner had always had a temper, and how his wife was the opposite, but that his father had been the same way—hot-tempered and loud—and Mr. Brandner took after his father.

She didn’t want to hear the first thing about Mr. Brandner slamming his children into walls, and neither did my grandfather.

The whole time, he’d been leaning against the kitchen sink, like he was following along, but when I asked him if he had anything to say, he just grumbled. Besides mowing the grass, that was his favorite thing to do, grumbling. Sometimes he actually sounded a little like his lawn mower.

He grumbled so much, you’d think he only had bones and organs inside him, not a single thought or word. He probably would have liked to grumble constantly, but in between it was sometimes necessary for him to brush his teeth or breathe or something like that.

It wasn’t true, though, that my grandfather was nothing but bones and organs. There was more to him. Every once in a while, he allowed himself some fun, which he couldn’t have done if he were really empty inside. Sometimes, for example, he would pretend that he was going to break the neighborhood rule against making noise on Sundays. He would haul the lawn mower out of the shed and set it in the middle of the lawn. When my grandmother rushed outside and started to lecture him on common decency, neighbors and following the rules, he would take up a screwdriver, begin tinkering with the mower and wink at me. And in that wink were all the questions, answers and complaints, and conversations he usually avoided.

That July evening, though, he didn’t wink, just shuffled out of the kitchen. Grandma also had something important to do in another room, probably some dusting. And me? I stood alone at the kitchen window. I couldn’t get Julia’s staring and Max’s silence out of my head. I still felt the same way half an hour later—sad and small—and so I decided to do something out of the ordinary. I called my father.

10

My father and I never spoke on the telephone when I was at my grandparents’. Even when he called for their birthdays, he didn’t want to talk to me, just had them pass on a message: Oh yeah, say hi to Mascha for me. Most of the time I didn’t mind. After a couple years, I got used to him wanting a few weeks alone every year to grieve for my mother. But then sometimes I would forget I’d gotten used to it, and in those moments, I missed him.

The day she died, my mother had been sitting in the garden drinking lemonade and swatting at wasps. She had breathed and breathed, and then she stopped. She’d vanished from our lives. And ever since, during summer vacations, I left my father alone, and came here to listen to music.

But after my grandparents left me in the kitchen, I couldn’t stand it anymore. I went to the guest room, which was my room in the summers when I stayed with my grandparents, and got my cell phone.

The room was so neat. It didn’t seem possible for me to sit down on one of the white-painted chairs and tell my father about Julia’s bruised stomach. So I got into bed, pulled the freshly washed covers over my head and made my call in the dark.

“Yes?”

“Dad, it’s me.”

“Is something wrong with Grandma?”

“What? No. Why do you think there’s something wrong with Grandma?”

“Well, why are you calling?”

“I have to tell you something.”

“All right. Tell me.”

“I met these two kids at the playground. I think they’re being beaten by their parents.”

“Do you think it, or do you know it?”

“Um, well, they have so many bruises. And the boy has a cut on his forehead and is very odd.”

“Mascha, you have to be careful. They could have been hurt some other way.”

“But I’ve also seen it.”

“What have you seen?”

“I looked through their window and saw Max being thrown against the wall by his father. He hit his head really hard.”

“Huh. Did you really see this?”

“Yes.”

“Mascha, this kind of thing should be taken care of by the police or Child Protective Services.”

“Well how are the people from Child Protective Services supposed to know they need to deal with it?”

“Someone else will tell them. If you’ve seen it, someone else must have, too. The neighbors, for instance, or the teacher, or the pediatrician. Eventually, someone will say something.”

“Eventually? Julia and Max will be dead.”

“That’s ridiculous, Mascha. People don’t just die that quickly.”

“But someone has to do something.”

“Yes, but not you. You are too young. You can’t do anything.”

People don’t just die that quickly, Dad had said. I couldn’t believe he’d said it. My father knew exactly how quickly—how unbelievably quickly—a person could die. How sometimes it could happen in a single second. Suddenly, there would be fewer cups of coffee drunk or beds made. What upset me even more was that my father was usually interested in other people, especially people who were having a difficult time. He only made movies where terrible things happened. Mostly they were movies about problems—about victims of train accidents, or suicides, or missing persons—basically they were movies about people who didn’t exist anymore. He made movies about people’s lives. He would go off with his camera and watch them as they grew sadder or older. Gawking, that’s what it was. My father was a gawker. The fact that all his watching and gawking didn’t make people any happier, well, he couldn’t do anything about that.

11

When I saw Julia and Max again, three days later, everything was just the way it always was. None of the mothers at the playground would have thought Max had recently had his head bashed into a picture frame. This time, the two of them were really cheerful. Even Max smiled a little from under the hair hanging in front of his face and talked, talked, talked. He’d never spoken when I’d seen him at the playground before, but it didn’t make that much difference, now that he did.

Because I couldn’t understand a word he said.

It wasn’t that much of a problem, because he wasn’t actually talking to me. It was just that there was no saying who he was talking to. He was standing right under the fort and, unfortunately, it looked like he was talking to the air. The air doesn’t answer when you speak to it though. Julia was doing the answering, except she wasn’t exactly answering him, but me. She had climbed up to sit with me on top of the fort, and started by answering a question I hadn’t even asked yet.

“You know who he’s talking to, Mascha? Pablo.”

“I don’t see anyone.”

“He’s his imaginary friend. He talks to him all the time.”

“That’s odd.”

“Daddy says so, too. He’s actually told Max he can’t talk to Pablo, but Max doesn’t care. He talks to him anyway. Sometimes they fight.”

“How would that work, exactly?”

“Max does it, believe me. So, do you want to play?”

“Play? Play what?”

“Let’s pretend we’re prisoners in the fort. We’ll have a contest, and whoever wins won’t be thrown to the bears. They’re down in the moat. The other one will be devoured.”

“Oh, okay. So what sort of contest?”

“We take turns saying things that are beautiful. First me, then you, then me again, then you. Whoever can’t think of anything first, loses. You know, gets thrown to the lions.”

“Or the bears.”

“Exactly.”

Max didn’t seem to want anything to do with lions and bears. He quit talking to Pablo, and trudged off, lost in his own world. Eventually, he sat down on the carousel. I didn’t really want to play Julia’s game either.

Thinking up beautiful things didn’t really fit with what I’d seen lately. But by the time Max had sat down on the carousel, Julia had begun with her beautiful things, and I didn’t have a choice. I had to play.

“The colors of duck wings, you know, the shimmery patches?”

“Hmm,” I said, “the fog on the way to school in the morning.”

“Being hugged, tightly,” said Julia.

“Listening to music with my dad,” I said.

“When Daddy’s not around.”

“When the batter of blueberry muffins slowly turns purple,” I said.

“When it’s morning and Max hasn’t wet the bed.”

“Um, okay,” I said. “When someone smells good after a bath.”

“A piece of melon.”

“The streetlights near our house.”

“Chickens,” said Julia.

“Chickens?” I asked. “Hmm. The moon. Does that count? I already said streetlights.”

“A picture with— Wait a minute, Mascha!”

And suddenly, just like that, the game was over. Julia jumped down from the fort and ran like a startled animal over to the carousel. I ran after her. Max had gotten himself into a fight, except that there was no one there for him to fight with, so he hit and shoved and throttled the air, and for the first time he was using words that I could understand: “Come here this instant!” he shouted. “Come right here and look at what you’ve done!” Max was red in the face. His hair was soaked with sweat and hung from his head in thick strands.

A couple of adults had gathered near the carousel, but not many, and most of the kids just sat in the sand still playing.

It was Pablo Max was shouting at, but since Pablo was invisible, the fight was eerie. Max growled, “Go on, go! Get out of here, why don’t you? You’ll be living in a home soon enough!” The mothers began to turn away and look after their children.

Julia stood blankly beside me, and I recognized the look on her face. It was the same one from a few days ago, at their house. She was absolutely still, but if you paid close attention, you could see she was shivering. You could hear her teeth going clackclackclackclackclack, muffled through her lips, which she pressed tightly together. Max continued to fight Pablo. I didn’t want to imagine what Pablo would have looked like, if he’d had an actual body, or what he would have felt like, if he’d had an actual heart. The things Max shouted got worse and worse. “You fat slob! You miserable fatso! We never wanted you!”

Julia stopped shivering. She went over to Max and took several blows that were meant for Pablo. With her thin arms, which were covered up by long sleeves even though it was summer, she tried to calm her raging brother. She did it very quietly and seriously, almost like a grown-up.

“Let me go, let me go,” Max screamed. “Leave me alone, you stupid cow!”

But Julia didn’t let him go. She held him tightly with all her strength and said, just loudly enough for me to hear it, too, “It’s okay, it’s going to be okay, Max.” And although it really wasn’t okay, wasn’t the least bit okay, Max slowly grew calmer in his sister’s arms, until the last few head-shaking bystanders went away, one by one. In the end, I was the only person left to notice the way Julia stroked her brother’s red face and quietly said, “You don’t want that, do you? You don’t want Daddy to hit you.”

12

What happened at the playground reminded me that, of all the things I didn’t like, the worst of them was being thirteen. There was nothing, absolutely nothing, you could do about the enormous zits on the sides of your nose. And you were expected to have a crush on someone, even if all the boys in your class looked and acted like ten-year-olds and all the older boys were totally out of reach. And no matter what you did, there was always some reason the grown-ups wouldn’t listen to you. You were still considered a little kid, so nothing you said could possibly be important. Not when you were thirteen.

The stupid thing was, the things I’d been saying actually were important. It would have been nice to have had someone who would listen to me, despite the fact that I was only thirteen. I hadn’t had much luck with my grandparents or my father, and I didn’t really know anyone else. But one day after Max’s fight, I decided to give it another try. I decided to head in the direction of the Brandners’ and see who I met along the way.

I ran into a lot of people, at least for Clinton. Three. Only I couldn’t really count the first one, this old guy on a bicycle who always tipped his greasy hat to me but never said a word. This time, too, he went by with nothing but a friendly whirr. The one who did speak to me was old Mr. Benrath, but somehow he didn’t count either, because he was getting senile and definitely wouldn’t be able to tell me anything about the Brandners.

“Mascha, would you like to come in? I’ll make us a lovely cup of tea, with real cream!”

“Not today, Mr. Benrath. I’ve got to go. But thanks.”

“Mascha, my child, just a small cup of tea, it won’t take but a minute, really.”

“No, really, Mr. Benrath. I can’t. I’ve got to go.”

“Nonsense. A small cup of tea. Are you coming in, then?”

“Next time, okay?”

Mr. Benrath was as old as everyone else in the entire neighborhood put together, and he stood all day long at his kitchen window, wrinkled, hacking and coughing. Whenever someone came by, he rushed out to his garden gate and asked with his last few ounces of breath if there was any chance they were headed to the newsstand, and if so, could they bring him back a pack of cigarettes.

Mr. Benrath must have lost a lot of money this way, because he would give money to pretty much anyone. Some kids who lived nearby really did buy cigarettes with the money, but they’d never have dreamed of giving them to Mr. Benrath.

Since I was too young to buy cigarettes for him, he was always inviting me in to chat and have tea with real cream. Till then, I’d always said no. I was afraid I would suffocate there in his smoke-filled living room and never be heard from again. I didn’t feel like suffering a smoky death, that day either, but even so, I turned and spoke to him.

“Mr. Benrath, do you know the Brandners? They live right across the way.”

“Christian and Helen, isn’t it? Right over there?”

“Do you ever hear them?”

“No, what do you mean?”

“But Mr. Benrath, you’re almost neighbors. You must be able to hear something!”

“Mascha, won’t you come in? I have tea.”

Just for a moment, Mr. Benrath didn’t look as confused as usual. His face seemed young and frightened, and he said to me, “Watch out, Mascha. They chased Elsa away because of that.” And then, after those few Elsa-seconds, he turned back into the old Mr. Benrath again, wrinkled and coughing and offering tea with cream. But I didn’t really hear him, because I had already said good-bye and gone on, even more confused than before.

13

If you’re running away from a conversation with Mr. Benrath and you keep going, you have no choice but to pass by Mrs. Johnson’s gate. Mrs. Johnson doesn’t smoke and uses regular half-and-half from the supermarket—at least that’s what I figured, because I’d never heard her say anything about cigarettes or cream. She has a different habit, which fits in very well with the neighborhood.

She tends her front garden.

But she doesn’t just plant it once a year, like everyone else here. She does it once a week. When the flowers she’s planted threaten to turn a week old, she rips them out of the ground and has her husband break up the soil so she can put in the next ones.

Because you can’t spend the entire day ripping out flowers, Mrs. Johnson spends the rest of her time trying to give away the flowers she’s ripped up to the same people who have just refused to buy cigarettes for Mr. Benrath. She was certainly the cheapest flower shop in the neighborhood, and, as usual, she didn’t spare me her sales pitch.

>

“Come, child. Take a few asters.”

“Grandma says we still have the ones from last week.”

“Nonsense. They’re yesterday’s news.”

“They look good, actually. Totally still red.”

“Here, you can just take ten.”

“They’re still fresh, really.”

“I’m putting a string around them for you.”

“The ones at home still look fresh. Mrs. Johnson, you know everyone around here.”

“It’s deceiving. They only look fresh, but in reality, they’re done for. Inside, they’re withering.”

“Mrs. Johnson, I want to ask you something.”

“Oh, you poor thing. It’s terrible what happened to your mother.”

Mrs. Johnson was the person in the neighborhood who had kept up with the you-poor-things and the how-terribles the longest. Everyone else had stopped because I never answered them. I would have liked to have answered her that time, though. I even wished she would stroke my hair, and if she had, I would have said, Stroke my father’s hair, too. He hasn’t had anyone do that for him in a long time. But I didn’t say anything because if I had, she would have given me three extra bouquets every time I passed.

Everyone in the neighborhood knew about my dead mother because my mother had died in, of all places, Clinton, right in my grandparents’ garden. She’d died in the garden with its picket fence, freshly painted, not a single slat broken. I think that was also the reason my father never wanted to come back here.

I hated that everyone knew about how she died. The people here hadn’t known my mother any better than they knew me. But as I stood there with Mrs. Johnson and listened to her go on about her flowers, I suddenly didn’t mind anymore. I decided to press her because I figured that a nosey person like Mrs. Johnson, who already knew everything about everyone, would know about the Brandners, too.

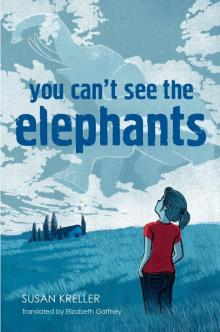

You Can't See the Elephants

You Can't See the Elephants