- Home

- Susan Kreller

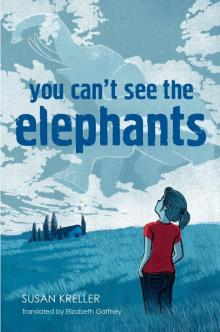

You Can't See the Elephants

You Can't See the Elephants Read online

G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

First published in the United States 2015 by G. P. Putnam’s Sons Books for Young Readers

Originally published in Germany 2012 by Carlsen Verlag GmbH under the title Elefanten sieht man nicht

Edited and published in the English language by arrangement with Carlsen Verlag GmbH

Text copyright © 2015 by Susan Kreller

English translation copyright © 2015 by Elizabeth Gaffney

The translation of this work was supported by a grant from the Goethe-Institut (Goethe-Institut ) which is funded by the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

G. P. Putnam’s Sons is a registered trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

ISBN 978-0-698-17779-6

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

Version_1

To all the others

—S.K.

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Acknowledgments

About the Author

THE ELEPHANT IN THE ROOM—a topic that everyone knows about but which, out of fear or a sense of discomfort, no one will discuss.

1

What happened in the blue house brought me a lot of dirty looks. It also brought me my father. The looks continued till the end of summer, but my father went away again after only two hours. I really would have liked it if he stayed a little longer. Maybe at some point he would have told me that what I’d done wasn’t wrong after all, or just slightly wrong, almost right. But all that he thought, there in my grandparents’ garden, was to ask if I couldn’t have done things a little differently.

Meanwhile, my grandmother was stirring her coffee cold and my grandfather was anxiously reading the Clinton Weekly. On the back page were the words Cool Waters Tempt Young and Old and Alfred Esser Appointed Chief of Fire Department. If you looked closely, you could see that my grandfather was trembling. The headlines quivered like birch leaves in a high wind, only there was no wind that afternoon. The sun beat down on the garden chairs, and there was nothing in the sky but two or three jet trails, small flaws in the ceiling of that glowing hot day.

After stirring fifty-odd times, till we didn’t think she could stir anymore, my grandmother finally stopped moving her spoon and said with a tortured expression that she could never go back to her exercise class because the others would talk. Siggy would talk, Trudy, even Hilda, who had always given her a ride to class. But she wasn’t responsible for her granddaughter’s behavior, was she? Grandpa lowered his newspaper, and my father growled something that began with thirteen and ended with old enough. I would have liked to have grumbled something back at him, but all I said was, “How long are you going to stay?”

2

Go play with the others.”

“Grandma, they won’t talk to me.”

“Not even Robert Bauer?”

“Won’t talk to me.”

“They won’t say anything?”

“They won’t say a thing. I end up just standing there. Can I go now?”

“Even Robert?”

“Uh-huh.”

“And the rest of them? The ones who used to meet by the old tree? What was it, a maple?”

“Grandma!”

“Them too? Well then, go see Trudy. She’ll be glad to see you.”

“She’s almost seventy. What am I supposed to do with her? And it was a sycamore tree.”

“Then go to the pool.”

“I’m not going to the pool. Everyone stares at me when I go by myself.”

“Then go see Trudy. She won’t stare.”

“Maybe because she’s half-blind.”

“Mascha!”

“Grandma!”

• • •

Clinton was the most boring town in the world. I may not have seen many towns in my life, but I’m still sure of that. It was truest in the neighborhood where my grandparents lived, the place where I’d spent all my summer vacations ever since my mother had died, seven years ago. It was a subdivision where all the paths that led to the redbrick houses curved in an orderly fashion, without either weeds or people. If you were from the city, like I was, you sometimes had the feeling that a train had just pulled away in front of you and left you standing all alone on the platform. The only time you saw people was when they washed their cars or went to their golf clubs or took care of the hydrangeas in their silent front yards.

“Hi Mascha!” they would say.

Or “How’s school?”

They were as old as they were scarce, these people. They wore tinted glasses and had white hairs on their arms, and had no kids. The few families that did have kids had either lived here forever or had just moved here in the past few years and didn’t really count. At least that’s the way it sounded when my grandmother gossiped about them with her friends. The other ones did count though. The ones who had always lived here. It was just that since you never saw them on the street, they counted very quietly.

It was so quiet that the silence pounded in my ears, though sometimes there would be someone mowing the grass, back and forth and back and forth, keeping it short and tidy, but never on Sundays. And there I stood, surrounded by all this lawn-mower silence, with nothing to do and all the time in the world.

At the beginning, I liked going to my grandparents’. I liked the playground and my little bike rides and even the cookouts with the neighbors and the dry crackers they sold at the pub

lic pool.

Of course I could have spent my time reading and keeping in touch with my friends back home, but sometimes you just can’t. The letters begin to blur, and then you stare at a fly on the wall or the useless clock in the kitchen that can’t even be bothered to move its hands.

There was simply no one there who I could do anything with. The old ones were too old, the young too young, and everyone in between—the ones who were my age—didn’t want anything to do with me. There wasn’t any real reason for it, was there? When the few kids who were my age met up by the old sycamore tree or in front of the supermarket, they didn’t send me away but they didn’t pay me any attention either. It was just that I wasn’t one of them. I was an even lower form of life than someone who had recently moved there. I was invisible. They knew I would only be there for the summer. And what I was doing there, no one knew for certain, especially me.

Even so, I was outside all the time, because inside, at my grandparents’, there was nothing, nothing at all, not even a grain of dust. When I was outside, I was always in one of two places: either the blue house—but more about that later—or the playground at the edge of the neighborhood. It was mostly sand, tons of sand, with a few swings, a seesaw and a carousel. Whenever I was at the playground—and I was almost always there—I sat with my earbuds and music player on top of a little wooden fort and listened to music while four-year-olds wobbled across a hanging bridge to a slide, avoiding me.

There were definitely more exciting things in life, but there was nothing really terrible about it. From the wooden fort, you could watch the mothers squinting their mother-squints whenever their kids used sand toys that didn’t belong to them. You could see the parents smoking and talking on their cell phones while their kids quietly stuffed sand in their mouths. The only reason their children didn’t fall off the fort was because I made a point of sitting on the high spot, which had a roof but no railings. It wasn’t much of a playground, but it was something. You couldn’t expect much more from that neighborhood.

Of course I was too old for the playground. I was three times the age of kids it was meant for. My grandmother was embarrassed that I went there so often. To be seen at a playground at the age of thirteen was an obvious failure. Mascha! At your age! But that’s the way it was. At just that age, I sat there, watched the hours creep across the sand. It was there that on the first Sunday of vacation, shortly before lunch, I met Julia and Max.

3

Julia and Max Brandner were the only people under seventy in the entire neighborhood who would talk to me. Though they took their time doing it and in the end, didn’t say much. But back at the beginning, they weren’t Julia and Max yet. They were just the girl and the boy. You couldn’t tell anything more about them.

The day the girl in the yellow shirt first showed up at the playground, the weather kept changing, like it couldn’t make up its mind. I was sitting at the top of the fort and had a roof over my head, so either way was fine with me. The rain fell straight past me, and the sunshine couldn’t get in.

At first, I hardly noticed them. I had already forgotten about the yellow spot of girl that moved slowly across the sand, followed by a second, sniffling, thicker spot, almost before I even saw them. All I saw was the rain, which was bright and smelled like sand and asphalt and the wrong town. I probably wouldn’t ever have noticed them, but then, while the boy sat on the carousel and spun wildly through the pouring rain, the girl climbed up to my fort. She sat beside me, but I pretended I didn’t see her. I turned up my music and concentrated on the rain and the boy on the carousel, who had gotten completely soaked and now began to throw a small temper tantrum. He was very fat. His stomach drooped in two equal rings over the waist of his sopping-wet pants. I pictured how he would look in a class photo: grim, as if the weight of the world were on his shoulders.

The girl was staring at me. I saw this from the corner of my eye, and I didn’t like it. I could feel her eyes on my skin. The rain continued to fall. I could hear the drops through my music. Maybe it was the rain that made me so restless, but suddenly I took out my earbuds, turned to the girl and looked her straight in the face.

That face.

It was very pretty, and my first feeling was envy, envy of such a pretty face. I imagined that face at school, happily surrounded by other faces, friends everywhere, playing together at recess, getting valentines. I imagined how well-liked, how not-invisible that face must be at school. The girl had long brown hair and green eyes with golden flecks. She had no more than five freckles on her nose, and the nose beneath the freckles was small with an upturned tip. Surely, I thought, that nose must delight its parents and its relatives, its friends and the authors of its love notes.

No one had ever been delighted by my nose. You could have used a thousand words to describe it, or you could just say that it was large and hooked.

Hooked nose, garden hose!

Mascha, freak, toucan’s beak!

On some people, a nose like mine may not have stood out, but on me, it did. First of all because I was short. I also had freckles—and more than just five, a lot more. My skin was more freckles than not. When you added it all together, the nose and being short and the freckles, I wasn’t going to win any beauty contests. At least that’s what my grandmother always said.

“Awful rain, huh?”

—

“I’ve never seen you here before. Is that your brother over there?”

—

“Did you just move here? You weren’t here last summer.”

—

“Argh!”

—

“What, don’t you talk?”

—

“Look, see that boy over there that’s fighting with the rain? Who looks like he wants to beat up the rain? Is he your brother or not?”

And then, as if the rain, too, was fed up with that wild downpour, poof, it just stopped. The kids weren’t ready for such a sudden change, especially not the boy, who grasped on to the carousel afraid and sat there motionless, as if he would dry off more quickly if he didn’t move.

And the strange yellow girl with the pretty face who had been sitting there the whole time with just a small corner of the fort’s roof over her head suddenly realized something that I had noticed a long time ago: the left side of her shirt was soaked. The damp yellow material looked green and tired. She lifted up the sweater and began to desperately squeeze out the wet part. I glanced over at the fat boy. He was talking to two other kids, who had appeared out of nowhere. But really, he wasn’t talking to them—he was staring at the ground.

“Baby elephant!” they shouted. “Baby elephant!”

In the meantime, the girl’s shirt just wouldn’t dry, so she yanked it over her head, accidentally pulling up the undershirt she wore beneath it. For a couple of seconds, her belly showed. It was just chance that I happened to look back at her at that exact moment. It was really just the blink of an eye. Then she pulled her shirt back down, making the giant purple-brown, yellow-rimmed marks on her belly disappear.

4

There are more ways in the world to get bruises than there are types of chocolate or television shows, and if you bothered to write down each of them, it wouldn’t make the bruises go away. You can get bruises while riding your bike if you whack your leg on the pedal. You can get them in the cafeteria if someone who wants their lunch first shoves you out of the way. You get them in winter when you fall down ice-skating, and even in the night when you bang your hip into the kitchen counter on your way to the fridge in the dark. Actually, there’s not a single moment in life when these marks aren’t lurking, blue and green, yellow and brown, around the very next corner.

What I couldn’t imagine, after I first met the girl at the playground, was how these giant bruises could have landed directly on her stomach, when they clearly belonged on other parts of her body. Maybe the girl had leapt from the high dive at the p

ool and not seen that there was a kickboard floating directly beneath her. Or maybe she had been lying down under an apple tree and a bunch of apples fell on her stomach, though to be honest I had never heard of such a thing happening.

I wasn’t satisfied with the kickboard or the apples. There was something else the girl was hiding beneath her shirt, and even if I didn’t know exactly what it was, I sensed it was nothing good.

But know? No, I couldn’t know.

I waited for the kids to come back to the playground.

Four long days I waited.

When I saw them again, the boy and the girl, it was just like the first time: the girl sat silently on the wooden fort, and the boy spun madly on the carousel. Seen that, done that, next. But this time, it wasn’t raining.

After a while, the fat boy jumped off the carousel and trudged over to the fort. When he came over, he just stood there, and if you think they finally said something, that boy and that girl, then you would be wrong.

Again the kids made fun of him.

“Hey, fatso!”

“So, how much do elephants eat?”

They weren’t very imaginative. The kids couldn’t think of anything worse to call him than elephant. The boy did flinch while trying to scrape a hole in the side of the fort with his fingernail.

What do you do when you see someone being bullied? Dad told me that he was once on a bus when a woman was being harassed by a couple of teenagers. The woman was just sitting there all by herself, and she had a big red birthmark on her face. The whole left side was red, and these kids came up with at least twenty insults to describe it. At some point my father couldn’t stand it anymore. He got up from his seat and sat down next to the strange woman and said, “Oh, hello, how are you? So funny to run into you here of all places.” The kids laid off her, but the woman wasn’t grateful for what my father had done.

“Leave me alone!” she shouted at him.

You Can't See the Elephants

You Can't See the Elephants